BRK SINCE 1972

It’s 1972. A group of young architects from Kraków are facing a formidable challenge. In the years to follow they are to determine the directions of development for the city which, since the Middle Ages – except for Nowa Huta, which was added from the east – has not changed its structure. The office is given significant powers, gains the trust of orderers, has unlimited access to municipal plans, employs the best specialists in the area of urban planning and architecture. It quickly becomes a leading enterprise in the field.

The windows of BRK’s office have a view over Kraków. On the one side, there’s the castle on the Wawel Hill, on the other – modern office buildings, together with Unity Centre, emerging in place of the legendary Szkieletor. Against this background, one can see the business-and-services development in the area of Dworzec Główny (Railway Station) and the elegant towers of St. Mary’s Basilica. In its immediate neighbourhood, there’s Al. Powstania Warszawskiego, which over the first decade of the 21st century has turned into an office-and-administration axis of the city. From this viewpoint, one can see very clearly how the new chapter of the city’s economic prosperity is evolving.

In the very heart of the evolving district, there are the famous “żyletkowce” (razor blades), i.e. office buildings built in the 1960s. On the fifth floor of one of them, a team of BRK architects develops new projects.

The windows of BRK’s office have a view over Kraków. On the one side, there’s the castle on the Wawel Hill, on the other – modern office buildings, together with Unity Centre, emerging in place of the legendary Szkieletor. Against this background, one can see the business-and-services development in the area of Dworzec Główny (Railway Station) and the elegant towers of St. Mary’s Basilica. In its immediate neighbourhood, there’s Al. Powstania Warszawskiego, which over the first decade of the 21st century has turned into an office-and-administration axis of the city. From this viewpoint, one can see very clearly how the new chapter of the city’s economic prosperity is evolving.

In the very heart of the evolving district, there are the famous “żyletkowce” (razor blades), i.e. office buildings built in the 1960s. On the fifth floor of one of them, a team of BRK architects develops new projects.

In the first decade of the 21st century, Kraków undergoes intensive economic, architecture and urban transformations. At the beginning of the second decade, the city already has an international renown. Kraków’s 9th place in the prestigious international ranking published by Tholons places the city at No. 1 in Europe and among the best in the world as a location for BPO, SSC, IT as well as R&D. In 2016, over 50 000 people are employed in these combined sectors. The city needs more office space, housing, public-use buildings. The city’s service centres are the driving force of the local economy and are stretching the housing and office infrastructure to its limits. In 2015 alone, the entire sector of international corporations has supplied the local market with an impressive amount of nearly 6 billion PLN. The peak of the construction market, however, is yet to come. The magic barrier of 1 million square metres GLA is forecast to be achieved by mid-2016. It is becoming clear that office space for shared services will continue to have a crucial impact on the economy for years to come, changing the panorama and the character of the capital of Małopolska.

A development of such intensity calls for architectural specialists. The skill of finding the right area for investment, manoeuvring in the thicket of bureaucratic procedures, effective architecture design that does not yield to temporary whims of fashion, and supervision of the construction process. BRK has supported its partners in the process of managing their capital across the entire investment-management spectrum for four decades now.

A development of such intensity calls for architectural specialists. The skill of finding the right area for investment, manoeuvring in the thicket of bureaucratic procedures, effective architecture design that does not yield to temporary whims of fashion, and supervision of the construction process. BRK has supported its partners in the process of managing their capital across the entire investment-management spectrum for four decades now.

In order to design new parts of the city, especially in a city like Kraków, it is not enough to have a creator’s vision. It is necessary to have the right combination of knowledge, experience, exposure to local reality, a sense of the local character of a location as well as intimate knowledge of local characteristics. Architects and urban designers who participate in the creation of the social fabric have to have the skill of the right assessment of the investment environment, while having a fresh outlook.

It is these qualities that have for decades defined the functioning of BRK, also now that it has been transformed into a modern architecture studio. Since 1972, the BRK team has designed and implemented several hundred entities and urban projects in the entire region. The experience gained over the years has been bringing positive results as BRK remains committed to its original architectural vision. With the start of the second decade of the 21st century, the office has gained a new image, in which tradition is one of the important dimensions of the work model.

Today’s BRK is a professional architectural enterprise, attentive to investors’ needs at all investment stages. New technologies, advanced processes, innovative materials, but most of all, enthusiasm and a fresh outlook of a dynamic architecture team – these are some of the attributes that wins new market sectors for BRK as well as the trust of new customers. It is worth taking a look at BRK’s achievements to date. The architecture studio has been operating under its carefully developed business strategy for over four decades now. BRK’s comprehensive approach to implemented projects is based on solid foundations. High quality of work and a multi-disciplinary approach to investment initiatives guarantee the investor a considerable approach and a certain predictability of the investment processes in successive implementation stages.

Today’s BRK is a professional architectural enterprise, attentive to investors’ needs at all investment stages. New technologies, advanced processes, innovative materials, but most of all, enthusiasm and a fresh outlook of a dynamic architecture team – these are some of the attributes that wins new market sectors for BRK as well as the trust of new customers. It is worth taking a look at BRK’s achievements to date. The architecture studio has been operating under its carefully developed business strategy for over four decades now. BRK’s comprehensive approach to implemented projects is based on solid foundations. High quality of work and a multi-disciplinary approach to investment initiatives guarantee the investor a considerable approach and a certain predictability of the investment processes in successive implementation stages.

Kraków. Poland. The 1970s. The era of bananowe spódnice [a type of skirt, popular in the 1970s], Led Zeppelin music, the spectacular investments of the Gierek era. Katowice inaugurate the famous Spodek. The first section of the Gierkówka – the ancestor of the A1 motorway – to Łódź is open, and in Warsaw one can see the recently inaugurated three, 24-storey sleek skyscrapers of the so-called Eastern Wall, between Marszałkowska, Aleje Jerozolimskie and Świętokrzyska. It is at that time that the Wojewódzkie Biuro Projektów is established in Kraków, out of the desire to catch up with its competitors. It’s 1972.

A group of young architects from Kraków are facing a formidable challenge. In the years to follow they are to determine the directions of development for the city which, since the Middle Ages – except for Nowa Huta, which was added from the east – has not changed its centralized and concentric structure. The office is given significant powers, gains the trust of orderers, has unlimited access to municipal plans, employs the best specialists in the area of urban planning and architecture. It quickly becomes a leading enterprise in the field in Poland.

There is lots of work ahead. Kraków’s crossroads require rebuilding, high-priority streets, strategic communication hubs. The growing city requires new districts, housing developments, public-use buildings. The last construction boom of the social-realist Nowa Huta did slow down but under Gierek cities gain new momentum. At the beginning of the 1970s they want to be the living monuments of a quickly accelerating epoch. The times favour growth and the office responds by providing ever more visionary projects.

There is lots of work ahead. Kraków’s crossroads require rebuilding, high-priority streets, strategic communication hubs. The growing city requires new districts, housing developments, public-use buildings. The last construction boom of the social-realist Nowa Huta did slow down but under Gierek cities gain new momentum. At the beginning of the 1970s they want to be the living monuments of a quickly accelerating epoch. The times favour growth and the office responds by providing ever more visionary projects.

At that time, working on a project translated to a multi-tier structure. Both metaphorically and literally. Task teams under the WBP brand developed an innovative method thanks to which time management is optimized in proportion to project complexity, without slowing them down at any of the stages. Occupying all floors of the modern office building, which, in years to come, will come to be referred to as “żyletkowiec”, architects were in a position to hand over to one another (across the building floors) the individual sections of the project, divided into thematic areas. The emerging construction or re-construction concept would go down the building floors, passing through the successive stages of architecture design, or would go up, depending on the needs and characteristics of the assignment.

Hence, one floor would be occupied by people in charge of accepting new orders and reviewing details of investment conditions in a given area. Another floor would hold working places for general architects. Others still would include urbanists, people responsible for detailed plans of technical infrastructure, water installations, electricity, and sanitary systems. The stage that followed was the valuation of projects and putting them within a specific timeframe.

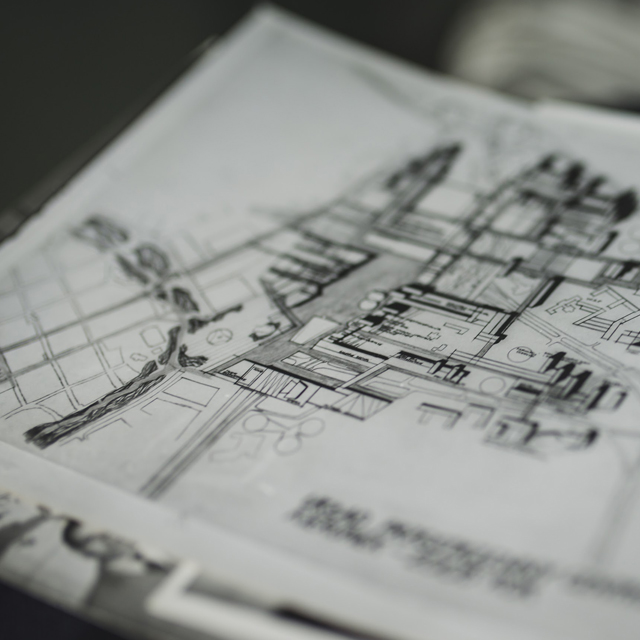

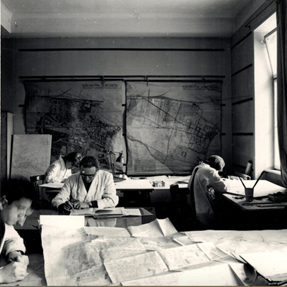

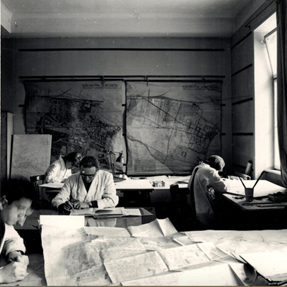

The work of individual WBP team members across the many floors of the building situated at Kordylewskiego 11 (used by the office since 1977) could serve as illustration of an exemplary film about planning visionary cities, in the spirit of the cult “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang. This, however, would only stand as a superficial comparison. There is something more to it. Architects dressed in white coats, bent over their drawing boards, laid down the new lines of city development, outlined the contours of new buildings and fine-tuned the details of building elevations. The photographs from that era that have survived in the archives of BRK remind one of the famous Bauhaus images taken in Dessau, which, today itself, can be found at Berlin’s Bauhaus-Archiv at Klingelhöferstrasse 14. This is the testimony of the golden age of architectural design, which till today has remained a reference point for generations of architects, proving that design is not only a craft dependant on the equipment in use, a method or software. In essence, architectural design is the outcome of the creative work of designers and, by being under the control of the author, leads to the creation of something unique, not infrequently, without a clear extant reference. The Bauhaus programme, aimed at organizing public life through the full use of architecture, which was in no way an example of art for art’s sake. The team at WBK had a similar objective, while designing, among others, the new complexes of housing and plans for cities and municipalities in the region.

The work of individual WBP team members across the many floors of the building situated at Kordylewskiego 11 (used by the office since 1977) could serve as illustration of an exemplary film about planning visionary cities, in the spirit of the cult “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang. This, however, would only stand as a superficial comparison. There is something more to it. Architects dressed in white coats, bent over their drawing boards, laid down the new lines of city development, outlined the contours of new buildings and fine-tuned the details of building elevations. The photographs from that era that have survived in the archives of BRK remind one of the famous Bauhaus images taken in Dessau, which, today itself, can be found at Berlin’s Bauhaus-Archiv at Klingelhöferstrasse 14. This is the testimony of the golden age of architectural design, which till today has remained a reference point for generations of architects, proving that design is not only a craft dependant on the equipment in use, a method or software. In essence, architectural design is the outcome of the creative work of designers and, by being under the control of the author, leads to the creation of something unique, not infrequently, without a clear extant reference. The Bauhaus programme, aimed at organizing public life through the full use of architecture, which was in no way an example of art for art’s sake. The team at WBK had a similar objective, while designing, among others, the new complexes of housing and plans for cities and municipalities in the region.

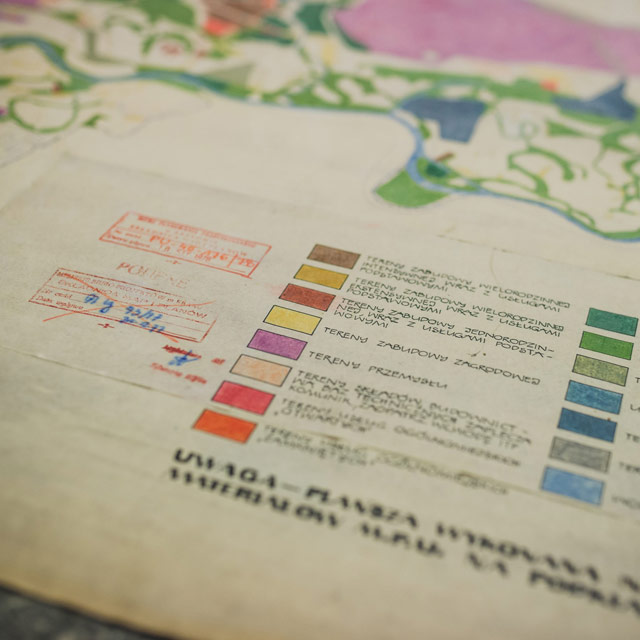

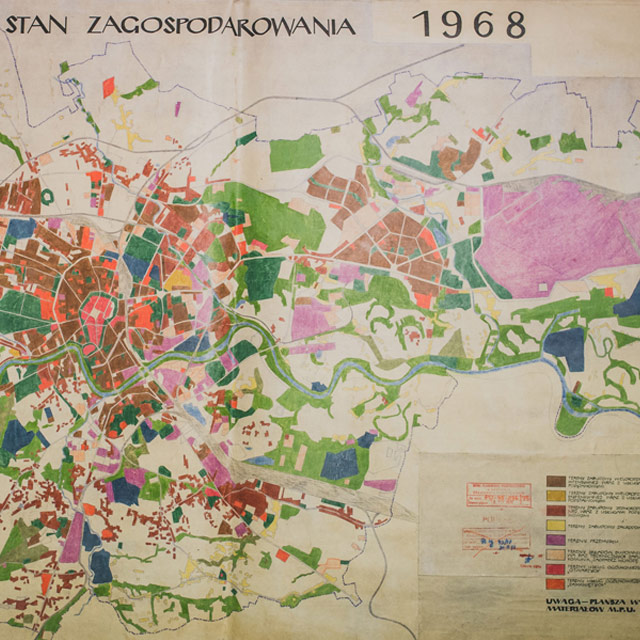

Sitting at tables covered with rolls of carbon paper, Rapidographs, paints, inks, compasses, rulers and set squares, architects would spend days and nights over the layers of maps, plans and layouts being developed. The laborious, Benedictine-reminiscent effort was about the scrupulous reproduction of reality and meticulously making their innovative ideas part of it. These calligraphic masterpieces drawn by the employees of the office inspire awe. Without access to computers or printers, they had to rely on their own manual and technical skills.

It is not by accident that the employees of the office enjoyed respect not only in Kraków but in various architectural studios across Poland. The scrupulous approach to various tasks had no match at the time. Buried in their work for hours, these architectural technicians proved that even if confronted with the most accurate machine, man is capable of proving his superiority. The precision of human effort resulting from the projects assigned to WBK had no equals. The same level of craftsmanship is passed on today to young architects, irrespective of the type of tools they use in everyday work. Over the first two decades, the office’s drawing boards, printers and plotters have seen the completion of several hundred ready projects, maps, projections, reports, plans, analyses and concepts.

It is not by accident that the employees of the office enjoyed respect not only in Kraków but in various architectural studios across Poland. The scrupulous approach to various tasks had no match at the time. Buried in their work for hours, these architectural technicians proved that even if confronted with the most accurate machine, man is capable of proving his superiority. The precision of human effort resulting from the projects assigned to WBK had no equals. The same level of craftsmanship is passed on today to young architects, irrespective of the type of tools they use in everyday work. Over the first two decades, the office’s drawing boards, printers and plotters have seen the completion of several hundred ready projects, maps, projections, reports, plans, analyses and concepts.

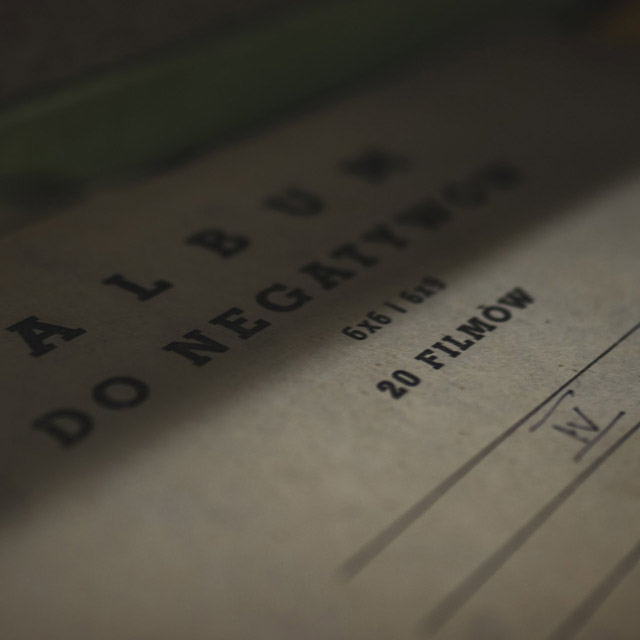

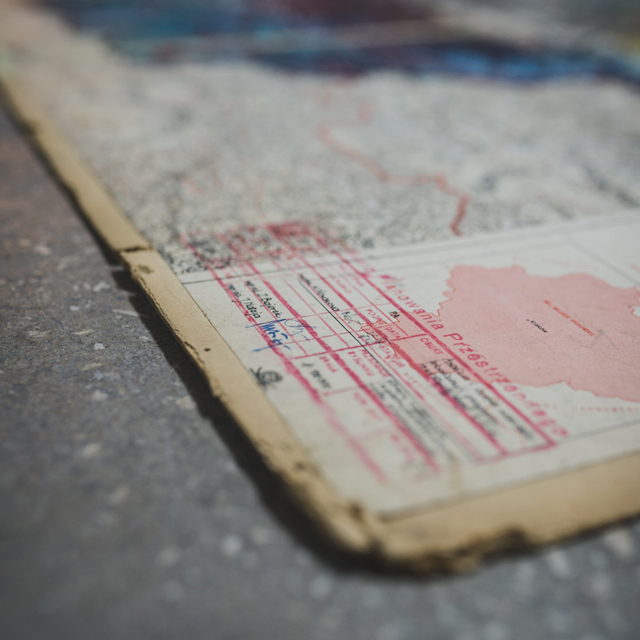

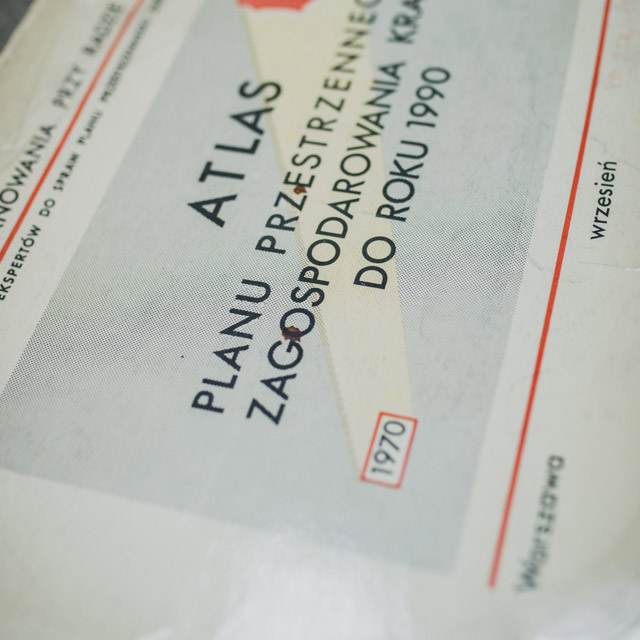

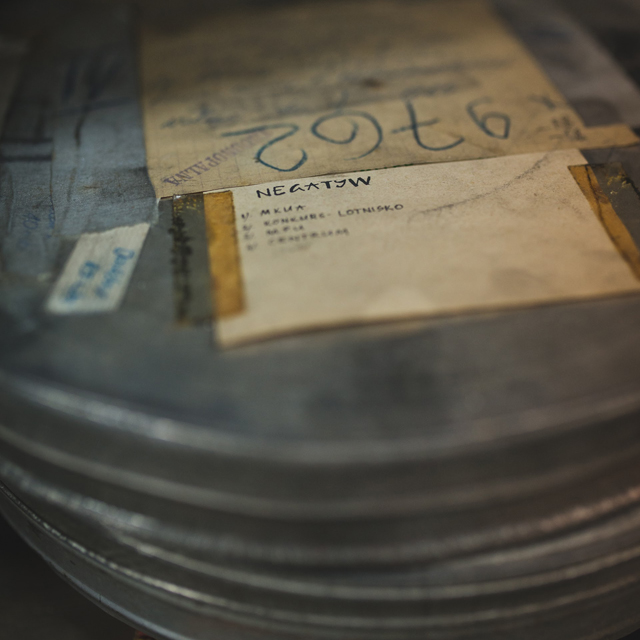

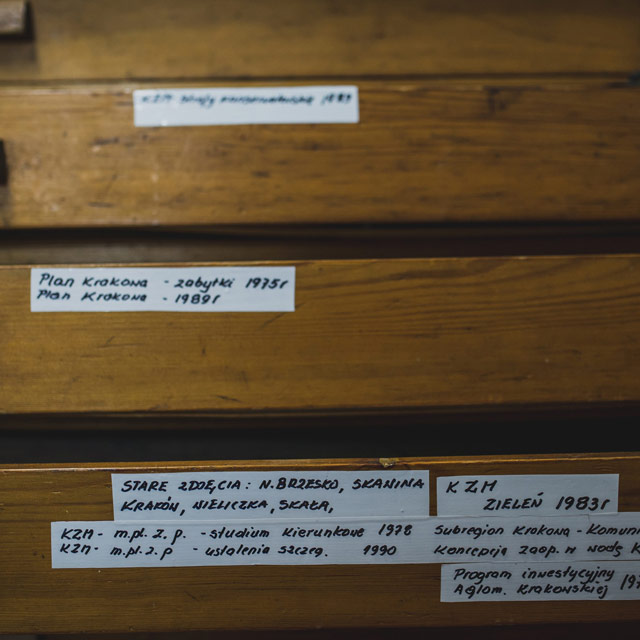

Browsing through the archives of BRK, with all the achievements of the employees of the time, perhaps the most impressive aspect is the mathematical accuracy in creating projects. Everything had to match in the documentation process; everything had to reflect the reality on site. In the archive of the office, which, many years later, almost begs to be turned into a unique museum, one can come across true gems of architectural effort involving entire generations of Kraków’s architects and urban planners. Stacked in rows, the large-format maps, meticulously glued to rectangular pieces of cardboard, rolls of local development plans, including comprehensive descriptions and legends, datasheets with numbers, albums with photos and films, with captions written in technical writing, including topographic details (at the time, there were two separate structures responsible for photography and printing). Each and every aspect of the painstaking work performed by the office’s professional teams of planners has been meticulously described, catalogued and archived. Thanks to the work of archivists, in charge of documenting the office’s legacy, one can see the true scale of material developed over the years by the representatives of Kraków’s architectural office who looked to the future without any inhibitions. Using waterproof inks, Rapidographs, markers, technical pencils, each and every item has been archived in its proper drawer, stamped with a label denoting timeframe and arranged according to geographic location.

Thanks to this information, we can browse through how the city changed as Kraków was undergoing dynamic transformation, but also investment in the areas of Chrzanów, Maków Podhalański, Jaworzno, Tuchów, Słomniki, Andrychów, Sucha Beskidzka, Proszowice, Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, Skawina, Zakopane, Oświęcim, Rabka-Zdrój, Trzebinia, Brzesko, Krzeszowice, Nowy Targ, Wieliczka and Limanowa. The images of successive industrial facilities built at the time rise before our very eyes, together with water and heat installations for housing developments gradually occupied by families, modernization of buildings, communication networks, roads and bridges. The voluminous files even include such rare items as meticulously accurate maps of the Polish Tatra Mountains, photographic documentation of Kraków’s Kazimierz or Podgórze districts of the time, aerial photos of villages surrounding Kraków, in place of which well-known housing developments were established, such as: Piaski Nowe, Kurdwanów, Prokocim, Prądnik Biały and Czerwony, Wzgórza Krzesławickie, Oświecenia, Ruczaj and Bieńczyce.

There is lots of work ahead. Kraków’s crossroads require rebuilding, high-priority streets, strategic communication hubs. The growing city requires new districts, housing developments, public-use buildings. The last construction boom of the social-realist Nowa Huta did slow down but under Gierek cities gain new momentum. At the beginning of the 1970s they want to be the living monuments of a quickly accelerating epoch. The times favour growth and the office responds by providing ever more visionary projects.

There is lots of work ahead. Kraków’s crossroads require rebuilding, high-priority streets, strategic communication hubs. The growing city requires new districts, housing developments, public-use buildings. The last construction boom of the social-realist Nowa Huta did slow down but under Gierek cities gain new momentum. At the beginning of the 1970s they want to be the living monuments of a quickly accelerating epoch. The times favour growth and the office responds by providing ever more visionary projects.At that time, working on a project translated to a multi-tier structure. Both metaphorically and literally. Task teams under the WBP brand developed an innovative method thanks to which time management is optimized in proportion to project complexity, without slowing them down at any of the stages. Occupying all floors of the modern office building, which, in years to come, will come to be referred to as “żyletkowiec”, architects were in a position to hand over to one another (across the building floors) the individual sections of the project, divided into thematic areas. The emerging construction or re-construction concept would go down the building floors, passing through the successive stages of architecture design, or would go up, depending on the needs and characteristics of the assignment.

Hence, one floor would be occupied by people in charge of accepting new orders and reviewing details of investment conditions in a given area. Another floor would hold working places for general architects. Others still would include urbanists, people responsible for detailed plans of technical infrastructure, water installations, electricity, and sanitary systems. The stage that followed was the valuation of projects and putting them within a specific timeframe.

The work of individual WBP team members across the many floors of the building situated at Kordylewskiego 11 (used by the office since 1977) could serve as illustration of an exemplary film about planning visionary cities, in the spirit of the cult “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang. This, however, would only stand as a superficial comparison. There is something more to it. Architects dressed in white coats, bent over their drawing boards, laid down the new lines of city development, outlined the contours of new buildings and fine-tuned the details of building elevations. The photographs from that era that have survived in the archives of BRK remind one of the famous Bauhaus images taken in Dessau, which, today itself, can be found at Berlin’s Bauhaus-Archiv at Klingelhöferstrasse 14. This is the testimony of the golden age of architectural design, which till today has remained a reference point for generations of architects, proving that design is not only a craft dependant on the equipment in use, a method or software. In essence, architectural design is the outcome of the creative work of designers and, by being under the control of the author, leads to the creation of something unique, not infrequently, without a clear extant reference. The Bauhaus programme, aimed at organizing public life through the full use of architecture, which was in no way an example of art for art’s sake. The team at WBK had a similar objective, while designing, among others, the new complexes of housing and plans for cities and municipalities in the region.

The work of individual WBP team members across the many floors of the building situated at Kordylewskiego 11 (used by the office since 1977) could serve as illustration of an exemplary film about planning visionary cities, in the spirit of the cult “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang. This, however, would only stand as a superficial comparison. There is something more to it. Architects dressed in white coats, bent over their drawing boards, laid down the new lines of city development, outlined the contours of new buildings and fine-tuned the details of building elevations. The photographs from that era that have survived in the archives of BRK remind one of the famous Bauhaus images taken in Dessau, which, today itself, can be found at Berlin’s Bauhaus-Archiv at Klingelhöferstrasse 14. This is the testimony of the golden age of architectural design, which till today has remained a reference point for generations of architects, proving that design is not only a craft dependant on the equipment in use, a method or software. In essence, architectural design is the outcome of the creative work of designers and, by being under the control of the author, leads to the creation of something unique, not infrequently, without a clear extant reference. The Bauhaus programme, aimed at organizing public life through the full use of architecture, which was in no way an example of art for art’s sake. The team at WBK had a similar objective, while designing, among others, the new complexes of housing and plans for cities and municipalities in the region.Sitting at tables covered with rolls of carbon paper, Rapidographs, paints, inks, compasses, rulers and set squares, architects would spend days and nights over the layers of maps, plans and layouts being developed. The laborious, Benedictine-reminiscent effort was about the scrupulous reproduction of reality and meticulously making their innovative ideas part of it. These calligraphic masterpieces drawn by the employees of the office inspire awe. Without access to computers or printers, they had to rely on their own manual and technical skills.

It is not by accident that the employees of the office enjoyed respect not only in Kraków but in various architectural studios across Poland. The scrupulous approach to various tasks had no match at the time. Buried in their work for hours, these architectural technicians proved that even if confronted with the most accurate machine, man is capable of proving his superiority. The precision of human effort resulting from the projects assigned to WBK had no equals. The same level of craftsmanship is passed on today to young architects, irrespective of the type of tools they use in everyday work. Over the first two decades, the office’s drawing boards, printers and plotters have seen the completion of several hundred ready projects, maps, projections, reports, plans, analyses and concepts.

It is not by accident that the employees of the office enjoyed respect not only in Kraków but in various architectural studios across Poland. The scrupulous approach to various tasks had no match at the time. Buried in their work for hours, these architectural technicians proved that even if confronted with the most accurate machine, man is capable of proving his superiority. The precision of human effort resulting from the projects assigned to WBK had no equals. The same level of craftsmanship is passed on today to young architects, irrespective of the type of tools they use in everyday work. Over the first two decades, the office’s drawing boards, printers and plotters have seen the completion of several hundred ready projects, maps, projections, reports, plans, analyses and concepts.Browsing through the archives of BRK, with all the achievements of the employees of the time, perhaps the most impressive aspect is the mathematical accuracy in creating projects. Everything had to match in the documentation process; everything had to reflect the reality on site. In the archive of the office, which, many years later, almost begs to be turned into a unique museum, one can come across true gems of architectural effort involving entire generations of Kraków’s architects and urban planners. Stacked in rows, the large-format maps, meticulously glued to rectangular pieces of cardboard, rolls of local development plans, including comprehensive descriptions and legends, datasheets with numbers, albums with photos and films, with captions written in technical writing, including topographic details (at the time, there were two separate structures responsible for photography and printing). Each and every aspect of the painstaking work performed by the office’s professional teams of planners has been meticulously described, catalogued and archived. Thanks to the work of archivists, in charge of documenting the office’s legacy, one can see the true scale of material developed over the years by the representatives of Kraków’s architectural office who looked to the future without any inhibitions. Using waterproof inks, Rapidographs, markers, technical pencils, each and every item has been archived in its proper drawer, stamped with a label denoting timeframe and arranged according to geographic location.

Thanks to this information, we can browse through how the city changed as Kraków was undergoing dynamic transformation, but also investment in the areas of Chrzanów, Maków Podhalański, Jaworzno, Tuchów, Słomniki, Andrychów, Sucha Beskidzka, Proszowice, Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, Skawina, Zakopane, Oświęcim, Rabka-Zdrój, Trzebinia, Brzesko, Krzeszowice, Nowy Targ, Wieliczka and Limanowa. The images of successive industrial facilities built at the time rise before our very eyes, together with water and heat installations for housing developments gradually occupied by families, modernization of buildings, communication networks, roads and bridges. The voluminous files even include such rare items as meticulously accurate maps of the Polish Tatra Mountains, photographic documentation of Kraków’s Kazimierz or Podgórze districts of the time, aerial photos of villages surrounding Kraków, in place of which well-known housing developments were established, such as: Piaski Nowe, Kurdwanów, Prokocim, Prądnik Biały and Czerwony, Wzgórza Krzesławickie, Oświecenia, Ruczaj and Bieńczyce.

The successes achieved by the office in the 1970s may be impressive but they certainly did not overshadow the tasks put before the architects employed by the office back in those days. Already in 1976, WBP is facing the first transformations. Following the first titles and awards won by the office, the name is changed to Biuro Planowania Przestrzennego (Spatial Planning Office).

Its task is to implement planning initiatives, both for the new area of the voivodeship as well as the neighbouring voivodeships. At the same time, new assignments arrive: not only from the area of Kraków but also neighbouring regions. WBP is now in charge of comprehensive planning-and-architecture for almost every bigger and smaller city of the Małopolska-Silesia subregion. The years that follow bring further success, unlike in many other architecture offices. As confirmed by Poland’s most prominent architecture experts, Kraków is growing with exceptional dynamics in those years. Exactly four years later, the office will come to face similar challenges resulting from the dynamic growth of the urban fabric of the capital of Małopolska (driven by the forces of the new economy, based on knowledge). It will turn out, also, that the experience and the model of managing an enterprise, developed in the early stages of functioning of the office, will become crucial on the eve of the second decade of the 21st century.

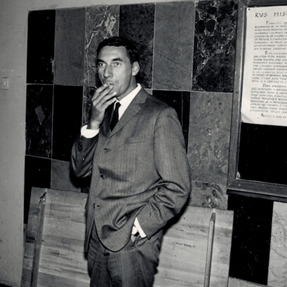

Back in 1977, Kordylewskiego 11 becomes BPP’s permanent head-office and takes over successive architects from Miejskie Biuro Studiów i Projektów w Krakowie (The City Office for Studies & Projects). This way, continuity is maintained (both in employment and know-how terms). Ryszard Kinda becomes the new director. The scent of the end of the opulent era of Gierek is already in the air, yet the office’s position remains unthreatened. For the period of only a few years, its planners and architects designed and effected comprehensive reconstruction of several dozen areas in Małopolska’s and Silesian cities as well as the construction of a significant number of buildings from scratch.

In 1979, operating on a grand scale, the team changes its name to Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa (Kraków Development Office). Since that moment, it will also be in charge of large-space-development plans for Kraków, as well as plans for administrative entities, study reports, engineering-and-architectural documentation, design of communication networks, infrastructure, even issues in the area of ecology, e.g. low-emission studies.

Kraków remains the most important city in the office’s portfolio. Over the decade that follows, the BRK team launches a number of projects which are important for the development of the city. Thanks to the laborious efforts of BRK, the landscape of large quarters of the city changes permanently, inclunding Bieżanów and Mistrzejowice, the housing developments on which, at that time, were the outskirts of the city – the areas of ul. Górnickiego, ul. Sądowa, the famous Hotel Forum at ul. Konopnickiej, the developments along ul. Armii Krajowej, as well as ul. Jasnogórska, Konopnickiej, Na Zjeździe, Opolska, Radzikowskiego, that were being developed. Also, the technical infrastructure of, among others, the Skawina and Płaszów mains services, the intermediate pumping station at Zakrzówek and smaller heating installations.

In the 1980s, BRK takes the first steps in the area of projects linked to ecology, among others environmental protection programmes – national and landscape parks, e.g. Ojcowski Park Narodowy (Ojców National Park) as well as concepts for developing the city greenery in protection zones around burdensome facilities. The awareness that ever larger parts of the country are put under protection results in more orders coming to Kraków’s experts: in cooperation with MPEC Kraków and EC Kraków, the office initiates the programme to close down in total 862 coal-powered boiler rooms in Kraków, develops and supervises the modernization programmes for the large boiler rooms covering housing developments such as Wieliczka, Balicka, Kościuszki, Zakłady Armatury, and the modernization of heat management at Dziecięcy Szpital Kliniczny in Prokocim (the Children’s Clinical Hospital in Prokocim).

In the 1980s, BRK takes the first steps in the area of projects linked to ecology, among others environmental protection programmes – national and landscape parks, e.g. Ojcowski Park Narodowy (Ojców National Park) as well as concepts for developing the city greenery in protection zones around burdensome facilities. The awareness that ever larger parts of the country are put under protection results in more orders coming to Kraków’s experts: in cooperation with MPEC Kraków and EC Kraków, the office initiates the programme to close down in total 862 coal-powered boiler rooms in Kraków, develops and supervises the modernization programmes for the large boiler rooms covering housing developments such as Wieliczka, Balicka, Kościuszki, Zakłady Armatury, and the modernization of heat management at Dziecięcy Szpital Kliniczny in Prokocim (the Children’s Clinical Hospital in Prokocim).

For a while, BRK’s reputation even stretches abroad. At the beginning of the 1990s, the office delivers projects for international clients. The increasing rank of the projects and the approaching grand modernization of the country results in successive modernizations. In 1991, BRK transforms into an employee-owned, commercial law company called Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa S.A. The new chapter in the history of the acclaimed office is about to start. The office now needs to quickly adapt to changing market conditions.

The era of computers and new planning technologies arrives. A ruler and a technical pencil are no longer the most important tools. The BRK planners gradually reduce their old habits and step into the world of computer design. It’s not easy. The technical limitations of the beginning of the “new era” do not make everyone’s work easy. The team, however, comes out as a winner from those trials. It succeeds in marrying traditional drawing techniques with computer-based design. Over a short period of time, the architectural office at ul. Kordylewskiego 11 becomes one of the most computerized offices in the region. At that time, plans and projects from the 1990s emerge, among others, the border crossing in Zwardoń, the national road section Szare–Zwardoń, one of Kraków’s crossroads, at Opolska–al. 29 Listopada, the study for the construction of the A4 motorway between Rzeszów and the state border; a multi-level crossroads Wielicka–Powstańców Śląskich, the crossroads between: Bieńczycka/Kocmyrzowska/Andersa, the Lilia Weneda Park, the reconstruction of ul. Karmelicka. Towards the end of the decade, the office develops the comprehensive plan for the development of Zamość, the study of conditions and directions of spatial development for the following municipalities: Wieliczka, Niepołomice, Rabka-Zdrój, Jabłonka, Tuchów, the local spatial development plan for Chechło-Południe and Chechło-Północ in Chrzanów, the plans for the village council of Zabierzów, Zabierzów Kochanów or the local spatial development plan for the PMO zone in Brzezinka.

Back in 1977, Kordylewskiego 11 becomes BPP’s permanent head-office and takes over successive architects from Miejskie Biuro Studiów i Projektów w Krakowie (The City Office for Studies & Projects). This way, continuity is maintained (both in employment and know-how terms). Ryszard Kinda becomes the new director. The scent of the end of the opulent era of Gierek is already in the air, yet the office’s position remains unthreatened. For the period of only a few years, its planners and architects designed and effected comprehensive reconstruction of several dozen areas in Małopolska’s and Silesian cities as well as the construction of a significant number of buildings from scratch.

In 1979, operating on a grand scale, the team changes its name to Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa (Kraków Development Office). Since that moment, it will also be in charge of large-space-development plans for Kraków, as well as plans for administrative entities, study reports, engineering-and-architectural documentation, design of communication networks, infrastructure, even issues in the area of ecology, e.g. low-emission studies.

Kraków remains the most important city in the office’s portfolio. Over the decade that follows, the BRK team launches a number of projects which are important for the development of the city. Thanks to the laborious efforts of BRK, the landscape of large quarters of the city changes permanently, inclunding Bieżanów and Mistrzejowice, the housing developments on which, at that time, were the outskirts of the city – the areas of ul. Górnickiego, ul. Sądowa, the famous Hotel Forum at ul. Konopnickiej, the developments along ul. Armii Krajowej, as well as ul. Jasnogórska, Konopnickiej, Na Zjeździe, Opolska, Radzikowskiego, that were being developed. Also, the technical infrastructure of, among others, the Skawina and Płaszów mains services, the intermediate pumping station at Zakrzówek and smaller heating installations.

In the 1980s, BRK takes the first steps in the area of projects linked to ecology, among others environmental protection programmes – national and landscape parks, e.g. Ojcowski Park Narodowy (Ojców National Park) as well as concepts for developing the city greenery in protection zones around burdensome facilities. The awareness that ever larger parts of the country are put under protection results in more orders coming to Kraków’s experts: in cooperation with MPEC Kraków and EC Kraków, the office initiates the programme to close down in total 862 coal-powered boiler rooms in Kraków, develops and supervises the modernization programmes for the large boiler rooms covering housing developments such as Wieliczka, Balicka, Kościuszki, Zakłady Armatury, and the modernization of heat management at Dziecięcy Szpital Kliniczny in Prokocim (the Children’s Clinical Hospital in Prokocim).

In the 1980s, BRK takes the first steps in the area of projects linked to ecology, among others environmental protection programmes – national and landscape parks, e.g. Ojcowski Park Narodowy (Ojców National Park) as well as concepts for developing the city greenery in protection zones around burdensome facilities. The awareness that ever larger parts of the country are put under protection results in more orders coming to Kraków’s experts: in cooperation with MPEC Kraków and EC Kraków, the office initiates the programme to close down in total 862 coal-powered boiler rooms in Kraków, develops and supervises the modernization programmes for the large boiler rooms covering housing developments such as Wieliczka, Balicka, Kościuszki, Zakłady Armatury, and the modernization of heat management at Dziecięcy Szpital Kliniczny in Prokocim (the Children’s Clinical Hospital in Prokocim).For a while, BRK’s reputation even stretches abroad. At the beginning of the 1990s, the office delivers projects for international clients. The increasing rank of the projects and the approaching grand modernization of the country results in successive modernizations. In 1991, BRK transforms into an employee-owned, commercial law company called Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa S.A. The new chapter in the history of the acclaimed office is about to start. The office now needs to quickly adapt to changing market conditions.

The era of computers and new planning technologies arrives. A ruler and a technical pencil are no longer the most important tools. The BRK planners gradually reduce their old habits and step into the world of computer design. It’s not easy. The technical limitations of the beginning of the “new era” do not make everyone’s work easy. The team, however, comes out as a winner from those trials. It succeeds in marrying traditional drawing techniques with computer-based design. Over a short period of time, the architectural office at ul. Kordylewskiego 11 becomes one of the most computerized offices in the region. At that time, plans and projects from the 1990s emerge, among others, the border crossing in Zwardoń, the national road section Szare–Zwardoń, one of Kraków’s crossroads, at Opolska–al. 29 Listopada, the study for the construction of the A4 motorway between Rzeszów and the state border; a multi-level crossroads Wielicka–Powstańców Śląskich, the crossroads between: Bieńczycka/Kocmyrzowska/Andersa, the Lilia Weneda Park, the reconstruction of ul. Karmelicka. Towards the end of the decade, the office develops the comprehensive plan for the development of Zamość, the study of conditions and directions of spatial development for the following municipalities: Wieliczka, Niepołomice, Rabka-Zdrój, Jabłonka, Tuchów, the local spatial development plan for Chechło-Południe and Chechło-Północ in Chrzanów, the plans for the village council of Zabierzów, Zabierzów Kochanów or the local spatial development plan for the PMO zone in Brzezinka.

Browsing through the archive at ul. Kordylewskiego 11, situated in the basement of the building, one feels fascinated by the meticulousness and the volume of work put into the creation of the photographic inventory of the housing complexes and investment areas, glued to cardboard, captioned with technical writing and stacked in separate boxes. Large rolls covered in dust contain rolls of hand-drawn maps, coloured and stored in tubes.

Next to the wardrobe with drawers full of design outlines and shelves with archive materials, there are boxes with modern iMac graphic stations. Each and every one of them is capable of storing the entire BRK archive on a single hard drive. On the eve of the two centuries, Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa enters the era of digital design across the spectrum. The team of architectural designers, furnished with ever more advanced computer equipment, continues to rely on rules defined over the years: precision, accuracy, responsibility for the project at all stages, technical compliance with real conditions. At this stage, however, BRK already has significant competition. Over the preceding few years, many professional architectural and design offices sprang up across Poland, which are equally successful at winning clients. The Kraków office, however, has something more to offer: a strong position built over decades, a large number of satisfied customers and a truly impressive portfolio accompanied by strong trust.

Hence the successive transformations towards a modern architectural enterprise. The key objective remains the same: to provide clients with comprehensive services starting from the design all the way to the final supervision of the investment. In 1994, the company issues shares, turning into an employee-owned business. This, however, proves to be an unfavourable solution and in 2001, the full package is purchased by Elżbieta and Kazimierz Koterba. Elżbieta Koterba becomes the new chairperson. Over this period, Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa S.A. receives new, lucrative offers from successive investors. The Koterba family decide not to sell the company, prevented by the positive sentiment to the company, where they have worked since university graduation. They make a decision instead to restructure the office and transform it into a family-owned business. An in-depth reorganization process of the pre-existing structures begins, bringing them up to date with modern standards. Employment goes down by half over the period of the decade that follows and part of the engineering tasks that used to be done internally is now outsourced. Employee remuneration goes up. The company starts two new pillars: planning and architecture. The design segment is from now onwards supervised by Elżbieta Koterba and the construction phase is overseen by Kazimierz.

The company is now equipped in the most state-of-the-art IT system in the region and the design process once again represents the highest standards. Employees have no difficulty obtaining full professional qualifications. The office is so efficient, in fact, that even the office renovation does not slow down its work. Successive orders flow in, among others an assignment to design a model city from the 1930s, Muzeum Wsi Lubelskiej, projects of both residential and non-residential buildings, among others at ul. Sławka, Kamienna and Wielicka in Kraków. At the time, BRK is also the first architectural office in the region which receives ISO certification and its structure is characterized and distinguished by full-time employment terms. Maintaining high standards of services makes it possible to maintain stable prices, allowing for adequate salaries for employees. The Koterba family are not after a quick profit; what matters to this fully-transformed, family-owned company is stable development and maintaining financial fluidity. The Koterba family are so committed to meeting this objective that, in 2008, the chairperson on the board at the time receives the Krakowski Dukat award (thus overcoming particularly strong stereotypes at the time concerning women in business), for the company manager category, awarded by Kraków’s Chamber of Trade and Commerce. Through her involvement in social projects, Mrs. Koterba receives special honours “for her services to the construction industry”, awarded by the Minister of Infrastructure in 2008. Over the years spent at BRK she builds her strong position in Kraków’s environment of architects and urban planners. She has received, among others, two 1st Degree Awards from the Minister of Construction and Spatial Development, multiple other honours and titles in architecture competitions, among others, for the central underground station in Warsaw, the Żabiniec housing development or the development of the Grunwaldzki Square in Wrocław. This series of successes is followed by the crowning achievement in the form of nomination to become Kraków’s Deputy Mayor for Development in 2011, putting an end to BRK’s structural division lasting for over two decades. The supervision of the company is now in the hands of the office’s natural successor in the Koterba family – the son of the resigning chairperson, Sebastian Chwedeczko. A new chapter in the history of the company opens. At the same time, Kazimierz Koterba becomes the chairman of the supervisory board of the office, supporting the company with his experience. Working at BRK from the very beginning of his professional career, Mr. Chwedeczko passes through all career stages in the family-owned business. He knows the company intimately, its structure, and is good at managing the new market reality that architecture offices are facing in the second decade of the 21st century.

Hence the successive transformations towards a modern architectural enterprise. The key objective remains the same: to provide clients with comprehensive services starting from the design all the way to the final supervision of the investment. In 1994, the company issues shares, turning into an employee-owned business. This, however, proves to be an unfavourable solution and in 2001, the full package is purchased by Elżbieta and Kazimierz Koterba. Elżbieta Koterba becomes the new chairperson. Over this period, Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa S.A. receives new, lucrative offers from successive investors. The Koterba family decide not to sell the company, prevented by the positive sentiment to the company, where they have worked since university graduation. They make a decision instead to restructure the office and transform it into a family-owned business. An in-depth reorganization process of the pre-existing structures begins, bringing them up to date with modern standards. Employment goes down by half over the period of the decade that follows and part of the engineering tasks that used to be done internally is now outsourced. Employee remuneration goes up. The company starts two new pillars: planning and architecture. The design segment is from now onwards supervised by Elżbieta Koterba and the construction phase is overseen by Kazimierz.

The company is now equipped in the most state-of-the-art IT system in the region and the design process once again represents the highest standards. Employees have no difficulty obtaining full professional qualifications. The office is so efficient, in fact, that even the office renovation does not slow down its work. Successive orders flow in, among others an assignment to design a model city from the 1930s, Muzeum Wsi Lubelskiej, projects of both residential and non-residential buildings, among others at ul. Sławka, Kamienna and Wielicka in Kraków. At the time, BRK is also the first architectural office in the region which receives ISO certification and its structure is characterized and distinguished by full-time employment terms. Maintaining high standards of services makes it possible to maintain stable prices, allowing for adequate salaries for employees. The Koterba family are not after a quick profit; what matters to this fully-transformed, family-owned company is stable development and maintaining financial fluidity. The Koterba family are so committed to meeting this objective that, in 2008, the chairperson on the board at the time receives the Krakowski Dukat award (thus overcoming particularly strong stereotypes at the time concerning women in business), for the company manager category, awarded by Kraków’s Chamber of Trade and Commerce. Through her involvement in social projects, Mrs. Koterba receives special honours “for her services to the construction industry”, awarded by the Minister of Infrastructure in 2008. Over the years spent at BRK she builds her strong position in Kraków’s environment of architects and urban planners. She has received, among others, two 1st Degree Awards from the Minister of Construction and Spatial Development, multiple other honours and titles in architecture competitions, among others, for the central underground station in Warsaw, the Żabiniec housing development or the development of the Grunwaldzki Square in Wrocław. This series of successes is followed by the crowning achievement in the form of nomination to become Kraków’s Deputy Mayor for Development in 2011, putting an end to BRK’s structural division lasting for over two decades. The supervision of the company is now in the hands of the office’s natural successor in the Koterba family – the son of the resigning chairperson, Sebastian Chwedeczko. A new chapter in the history of the company opens. At the same time, Kazimierz Koterba becomes the chairman of the supervisory board of the office, supporting the company with his experience. Working at BRK from the very beginning of his professional career, Mr. Chwedeczko passes through all career stages in the family-owned business. He knows the company intimately, its structure, and is good at managing the new market reality that architecture offices are facing in the second decade of the 21st century.

Over the last few years, BRK architects have successfully implemented bold architecture concepts. Several of their buildings have become Kraków’s new showpieces and recognizable points on the city map.

One of the much-appreciated realizations is Centrum Energetyki AGH (the AGH Centre for Energy) situated on Czarnowiejska. The diamond black and the composition of the building – reminiscent of a rectangular block of coal with vibrant lemon distinguishing features – is a successful example of modern thinking blended with classical form. The Centre for Energy relates directly to the surrounding environment, constituting the logical completion to the ecosystem of university buildings within the AGH campus. Situated along ul. Czarnowiejska, i.e. one of the axes of the university campus, it is becoming one of the showcases for one of the best technical universities in Poland. Inside CE AGH there are as many as 38 lab facilities, equipped in state-of-the-art equipment for experts in several disciplines linked to energy.

Yet another project co-developed by BRK is the much-praised complex of office buildings called Bonarka for Business (B4B), situated between Puszkarska, Sławka and Kamieńskiego. Bonarka for Business, in its complete version, is a complex of 10 A-class buildings with a total area of 95 000 sq. m., developed in a carefully planned urban layout. To date, between 2011-2015, buildings A, B, C, D, E, F have been built. In 2016– 2020, the remaining buildings G, H, I, J will be put into operation.

The architecture concept and the building project for the development of the B4B buildings was developed by Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa in cooperation with IMB Asymetria. BRK architects have thus created attractive office spaces for more than ten thousand employees. In the already existing B4B buildings, renowned international companies have already opened their branches, including: Alexander Mann Solutions, State Street, Euroclear, Lufthansa Global Business Services and RWE. Over the period of six years, the once-forgotten part of Kraków changed beyond recognition. The heaps of sand, waste, thickets and boggy terrain once surrounding the railway tracks of the Kraków Bonarka station have turned into an elegant, vibrant campus for global companies. The rectangular shapes of buildings, bold lines, facades reminiscent of industrial brick, but also covered with white, gleaming chessboard-shape windows and screens.

The most spectacular idea of the architects was to use the characteristic factory chimney remaining from the dismantled plant as the distinctive, well-lit point of reference for B4B, including the neighbouring shopping complex.

Yet another original idea is the square with the area of over six thousand square metres, including fountains, greenery, benches and decorative lighting, developed as a communication tract between the shopping gallery and the office buildings. In line with the original idea, it has become a popular meeting venue and a place of rest for, among others, employees.

Experts unanimously believe that BRK’s modern design of Bonarka 4 Business makes a very good impression. It is no surprise, therefore, that its creators have won multiple awards for the project, including “Kraków – mój dom” (2014), “artURBANICA” (2012), a title awarded for quality, in public-space category, or “Prime Property Prize Małopolska” (2013) in the office-building category, as an example of a modern building meeting the requirements of even the most demanding tenants.

The next investment designed by BRK which has succeeded in becoming a permanent part of the commercial landscape of this city, with nearly a million inhabitants, is Galeria Bronowice, the biggest shopping complex in the north-western part of Kraków. According to the original concept, its architecture was to “relate to the style of Young Poland, inextricably linked to Kraków, in a subtle and balanced way”. Even though there are multiple restrictions related to the development of shopping centres, the centre developed within the project represents about 60 000 square metres of space.

A lot of emphasis was put to specific lighting conditions across the building. The spaces that have been developed are lit mostly with daylight (thanks to the use of large-format windows in the roofing and a range of different skylights). Thanks to this solution, unlike in other shopping centres, Galeria Bronowice has a much better influence on how clients, employees and guests feel inside.

Designers have used individual lighting programmes, including the expression wall (ściana ekspresyjna), the casing for the posts next to the entrance to the parking area as well as lighting for staircases. Conscious efforts were made to incorporate the lighting elements into the building elevation in such a way as to emphasize the unique form of the building and reflect its character. What comes as a surprise to many are many other interior décor items, such as Young Poland decorative frieze cut-outs, wall sections and glazings.

It’s a success. Today, Galeria Bronowice is one of the most important addresses on the commercial map of Kraków. Brands such as Auchan, Saturn, dozens of shops, boutiques, coffee shops and restaurants attract thousands of customers every day, mainly from the north of the city, but also from Olkusz, Chrzanów, Trzebinia, Krzeszowice, Skała and Wolbrom.

Yet another project co-developed by BRK is the much-praised complex of office buildings called Bonarka for Business (B4B), situated between Puszkarska, Sławka and Kamieńskiego. Bonarka for Business, in its complete version, is a complex of 10 A-class buildings with a total area of 95 000 sq. m., developed in a carefully planned urban layout. To date, between 2011-2015, buildings A, B, C, D, E, F have been built. In 2016– 2020, the remaining buildings G, H, I, J will be put into operation.

The architecture concept and the building project for the development of the B4B buildings was developed by Biuro Rozwoju Krakowa in cooperation with IMB Asymetria. BRK architects have thus created attractive office spaces for more than ten thousand employees. In the already existing B4B buildings, renowned international companies have already opened their branches, including: Alexander Mann Solutions, State Street, Euroclear, Lufthansa Global Business Services and RWE. Over the period of six years, the once-forgotten part of Kraków changed beyond recognition. The heaps of sand, waste, thickets and boggy terrain once surrounding the railway tracks of the Kraków Bonarka station have turned into an elegant, vibrant campus for global companies. The rectangular shapes of buildings, bold lines, facades reminiscent of industrial brick, but also covered with white, gleaming chessboard-shape windows and screens.

The most spectacular idea of the architects was to use the characteristic factory chimney remaining from the dismantled plant as the distinctive, well-lit point of reference for B4B, including the neighbouring shopping complex.

Yet another original idea is the square with the area of over six thousand square metres, including fountains, greenery, benches and decorative lighting, developed as a communication tract between the shopping gallery and the office buildings. In line with the original idea, it has become a popular meeting venue and a place of rest for, among others, employees.

Experts unanimously believe that BRK’s modern design of Bonarka 4 Business makes a very good impression. It is no surprise, therefore, that its creators have won multiple awards for the project, including “Kraków – mój dom” (2014), “artURBANICA” (2012), a title awarded for quality, in public-space category, or “Prime Property Prize Małopolska” (2013) in the office-building category, as an example of a modern building meeting the requirements of even the most demanding tenants.

The next investment designed by BRK which has succeeded in becoming a permanent part of the commercial landscape of this city, with nearly a million inhabitants, is Galeria Bronowice, the biggest shopping complex in the north-western part of Kraków. According to the original concept, its architecture was to “relate to the style of Young Poland, inextricably linked to Kraków, in a subtle and balanced way”. Even though there are multiple restrictions related to the development of shopping centres, the centre developed within the project represents about 60 000 square metres of space.

A lot of emphasis was put to specific lighting conditions across the building. The spaces that have been developed are lit mostly with daylight (thanks to the use of large-format windows in the roofing and a range of different skylights). Thanks to this solution, unlike in other shopping centres, Galeria Bronowice has a much better influence on how clients, employees and guests feel inside.

Designers have used individual lighting programmes, including the expression wall (ściana ekspresyjna), the casing for the posts next to the entrance to the parking area as well as lighting for staircases. Conscious efforts were made to incorporate the lighting elements into the building elevation in such a way as to emphasize the unique form of the building and reflect its character. What comes as a surprise to many are many other interior décor items, such as Young Poland decorative frieze cut-outs, wall sections and glazings.

It’s a success. Today, Galeria Bronowice is one of the most important addresses on the commercial map of Kraków. Brands such as Auchan, Saturn, dozens of shops, boutiques, coffee shops and restaurants attract thousands of customers every day, mainly from the north of the city, but also from Olkusz, Chrzanów, Trzebinia, Krzeszowice, Skała and Wolbrom.

Already in 2013 Forbes grants BRK a prestigious nomination to Forbes Diamonds (Diamenty Forbesa), assessing its assignments at over 9 million PLN, and the value growth at about 60% over a period of about 2 years since the new chairman takes over (2009-2011). The years that follow bring even more dynamic development, significantly increasing the portfolio of orders.

BRK now employs a team of 25 employees with very high qualifications, in very different age groups. The pillar of the office is young specialists, talented graduates of the best architecture universities in Poland and abroad. The company’s great asset is their cooperation with persons who have worked for BRK much longer, who provide their younger colleagues with expert advice and experience. The marriage of young energy and long-standing experience at the Kordylewskiego offices actually works. This is something that doesn’t always work out in other architecture offices. While many of them are in the process of building well-integrated teams and stable structures, BRK has had them for years now, supplementing tried-and-tested experts with talented representatives of the younger generation.

Even though he represents the younger generation of architects, Sebastian Chwedeczko makes a conscious effort to combine the two generations of architects employed at BRK in such a way so that they come as an inspiration for one another and do not try to subjectively push their visions forcibly. He believes that everyone has the creative potential but the success of a project depends on the successful clashing of the best concepts and developing on this basis their own, unique style. The distinctive characteristic of BRK for the near future is the combination of modern solutions, techniques and projects with classical form, tried-and-tested operating mode, and the ability to control the logistics chaos which one often comes across in projects that are implemented in haste.

Chwedeczko keeps repeating that investors particularly value cooperation with companies that are capable of managing their investments at all levels and at all stages of work. For this reason, the objective of BRK remains to provide adequate attention to projects, from the first to the last minute of its implementation. This is how BRK operated while working on the AGH Centre for Energy, the Bonarka 4 Business office complex as well as the Bronowice Shopping Centre.

Despite the passing of time, BRK remains the key player in the competition for the most spectacular projects implemented in the south of Poland. Thanks to its legacy and the history of taking responsibility for the success of strategic investments in the region, it enjoys unrelenting success. Similarly to the era of technical pencils, violet carbon paper and cardboard rolls, now, in the age of AutoCAD or futurist 3D models – is a living testimony to quality and continuity of professional craftsmanship.

Even though he represents the younger generation of architects, Sebastian Chwedeczko makes a conscious effort to combine the two generations of architects employed at BRK in such a way so that they come as an inspiration for one another and do not try to subjectively push their visions forcibly. He believes that everyone has the creative potential but the success of a project depends on the successful clashing of the best concepts and developing on this basis their own, unique style. The distinctive characteristic of BRK for the near future is the combination of modern solutions, techniques and projects with classical form, tried-and-tested operating mode, and the ability to control the logistics chaos which one often comes across in projects that are implemented in haste.

Chwedeczko keeps repeating that investors particularly value cooperation with companies that are capable of managing their investments at all levels and at all stages of work. For this reason, the objective of BRK remains to provide adequate attention to projects, from the first to the last minute of its implementation. This is how BRK operated while working on the AGH Centre for Energy, the Bonarka 4 Business office complex as well as the Bronowice Shopping Centre.

Despite the passing of time, BRK remains the key player in the competition for the most spectacular projects implemented in the south of Poland. Thanks to its legacy and the history of taking responsibility for the success of strategic investments in the region, it enjoys unrelenting success. Similarly to the era of technical pencils, violet carbon paper and cardboard rolls, now, in the age of AutoCAD or futurist 3D models – is a living testimony to quality and continuity of professional craftsmanship.